Querrin Pier and Fishing

Querrin Pier was built when the Shannon Commission was set up to build a series of piers on the River Shannon. Construction in 1842 started on the 1st April and was completed on the 31st December. Construction was carried out by Messrs. Sykes and Brookfield, who had an average of 45 men employed daily on the project. The limestone ashlar fronting stone came by horsecart from a quarry in Killimer. The total cost of the building of the pier was £1,160-5s-0d, of which 50% was paid by the residents of Querrin House. The Shannon Commission left 5 beautiful granite stones around Querrin pier with S.C. engraved on them. After the Shannon Commission had built the piers they went out of existence and the piers were handed over to the Board of Works. The piers were built as the fishing industry was a very successful enterprise.

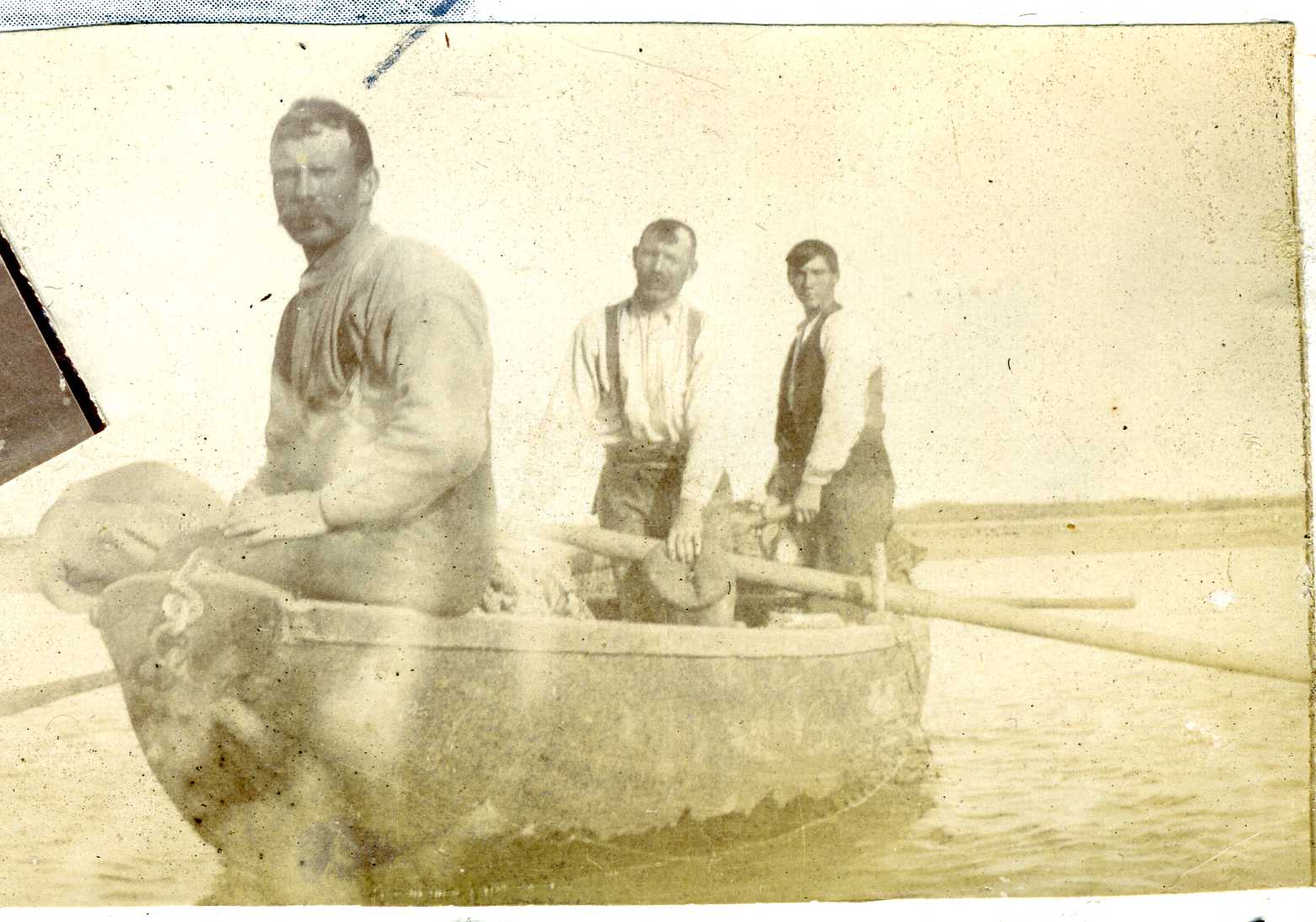

The river Shannon was full of fish and the part of the estuary just off Querrin is about 4 miles broad from Querrin to Beal Stand in Kerry and 10 miles long from Kilrush to Loop Head and is almost a lake. From the landing at Querrin 80 canoes (currachs) fished. Each of these was manned by 3 men (240). It also had 14 fishing boats carrying sail with 4 men each (56) and 3 turf boats with crews of 3 men (9). That is a total of 305 men working directly from the pier. These men were almost "amphibious", half farmers, half sea men. A good deal of money was made from fish and splendid food was secured. They were past masters of the art of curing fish. Even up to the 1960s and maybe longer in Kilkee, the Western farmers fished and cured mackerel for sale. They sold them in spring. The colour was golden and the flesh hard. Now it is done no more. I have seen Randal Counihan cure mackerel using the old traditional skills of hang-smoking in a very authentic oil barrel made to act like a smoke house burning the traditional wood and the smoked mackerel were delicious.

The tithes were collected from the fishermen when they came ashore in the mornings. One tenth of their catch was claimed and taken by the Protestant minister. A local story tells of one such minister called Whitty. This Whitty resided in Kilrush. He came with his men who had horse and cars with creels to take away the fish. That went on for some time until one morning a man named O'Connell said Whitty would get no fish that day. O'Connell was a powerful man and so was Whitty who also had the mighty British laws behind him. The landing place for canoes was a sandy creek; the bows of the canvas boats would rest on the beach. Apparently there was an argument and they caught holds and wrestled. O'Connell knocked Whitty, whose head fell towards the water. O'Connell kept his head under water and would have drowned him only for the intervention of the other fishermen. I wonder was he an ancestor of Michael O'Connell, our resident local historian! Whitty went home and never came or sent for fish again. One tenth of the corn and straw grown was also taken. The corn was stacked in the haggard of Querrin Lodge at the top of the hill. During World War 1, hay and straw left from Querrin pier bound for Europe to help feed and bed the horses used during the war.

The fishing has gone long ago; the fishermen have dwindled to a couple of men who fish for salmon and a very odd time other fish. The last of the local salmon fishermen was Martin McMahon and he has just recently hung up his boots due to the onerous regulations. All along the northern side of the peninsula from Loophead to Moveen the farmers fished for mackerel and cured the surplus for sale. That has all gone. At Carrigaholt there were three turf boats carrying turf and farm produce to Limerick. They are gone. Fifty years ago there were three fishing sailing boats operating from Carrigholt, they are gone and not replaced.

The turf boats were used to bring turf to the city of Limerick as late as 1929-1933. They also brought corn and butter to be sold in the city. The owners accompanied the goods on the boats. In the last century little meat was eaten except bacon. In the early 1900s eggs were bought at 1d (old penny) per dozen. The districts were called plough lands.

The herrings were another great industry and the ones caught in Querrin were known for their delicious taste. They are generally small but very nice to eat. They are, and were, noted for their quality. They were stored in barrels after being cleaned and layer upon layer was laid down with salt. They were then exported .The local fishermen cured their own herring and they hung from the roofs on string. I remember seeing them and eating them in the 1950s/60s. As and when a herring was needed it was pulled off the string leaving the head behind. The herring was then steeped in water overnight to get rid of some of the salt before been eaten. Herrings are still caught with a net a few times of the year to keep the tradition going. When men fished herrings from their currachs they cooked suppers of them at sea by roasting over turf fires as they sometimes stayed out overnight to get a good catch. They brought a small pot with embers of turf ready to use when needed. The herring was a great form of food and helped build a layer of fat on these hardy men. The sail fishing boats went into the Atlantic and fished along the coast. Doonbeg bay was a rendezvous for the fleet. The large and coarse fish were caught in large quantities and sold at good prices. This industry added to the wealth of the land and made them prosperous.

The sons were all trained to row boats, and so were all the men of Querrin. Agriculture was limited to growing corn, potatoes, cabbage for home use and wheat for sale. They grew flax for personal clothing, sheets, ticks, bolsters and table cloths. The men wore bandied cloth (coarse linen) shirts; declared by Dr. Knipe, the great German priest doctor, to be the best under clothing in the world. Being coarse it warmed the skin by friction. A fine linen front was fitted in the front and neck for Sunday wear. The other garments were of wool, except corduroy breeches, such as báiníns, a waist-coat with sleeves of flannel, a flannel back and lining. Several báiníns were worn, a frieze body coat covered that, flannel drawers, long stocking of grey wool and knee britches. Cloigíní or low shoes' with only one eye hole at each side, a tall hat topped it all. The coat was cutaway style dressed with a white shirt, with gladstone collars and a black silk scarf. When travelling a heavy frieze overcoat was worn and generally lined with flannel. A days rain would not penetrate it. It would take a giant to carry it when wet. For riding the coat was split high up, like the coats Guinness's dray men used to wear. Imagine one of these men walking back in the day, a king in his cutaway with two brass buttons at back, a relic of the sword belt days, knee breeches with three brass buttons on each leg outside and bow of brawn ribbon, accompanied by his blackthorn.

They hurled and played their matches on Querrin Head, a strip of sandy land half a mile long or so between the Shannon and a Creek. They used to cross the Shannon to hurl the Kerryman on Beale Strand at other side of estuary. They tell a story of a man from Querrin, one James Haugh (Séamas Poch Anáirde). At a contest once on Beale strand he stuck his heel in the sand and struck the ball nine times in the air before it struck the ground.

In Querrin their winter amusements were dancing and fencing. Kerrymen came across to teach those arts. The crowd went to each house in turn. They held contests in stories, legends, history, and poetry etc. The Kerry visitors were all considered well up and it would take a smart fellow to put one down, or even hold his own with them. Up to the Famine it was a thriving district. They had their own sailing boats built at Querrin. Nets were homemade from flax thread grown and made from home grown flax and woven at home. After the famine only a few fishermen survived in the Querrin area and with the last of the salmon fishermen now gone, 2020 sees none left at all.